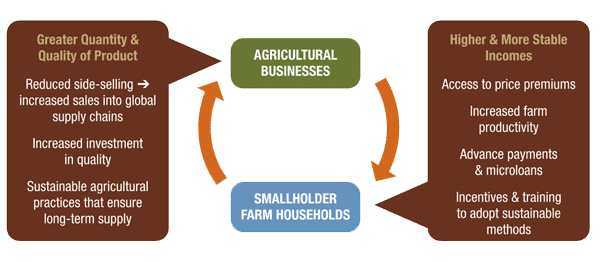

The mutually beneficial relationship between agricultural business, smallholder, and natural environment.

Note: In February, Root Capital published our inaugural Issue Brief on the emerging business case for financial institutions to conduct due diligence on the social and environmental practices of their borrowers and investees.

This is the second in a series that goes deeper on that social and environmental due diligence, addressing questions such as: What do we look for in the business we lend to, and why? How do we go about it? And how do smallholder producers and agricultural businesses in Africa and Latin America benefit, as well as upstream exporters, processors, retailers, and consumers worldwide?

Readers of this blog likely already know that, of the 2.6 billion people who survive on less than $2 per day, 75 percent live in rural areas and rely on agriculture for their livelihood. They are constrained by lack of access to markets, farm inputs, agricultural training and technology, and credit. They resort to survival measures such as illegal logging and slash-and-burn agriculture that perpetuate a cycle of poverty and environmental degradation.

Often, agricultural businesses and producer associations can help smallholder farmers overcome these barriers. They do so by establishing a mutually beneficial relationship with smallholders and by supporting their adoption of sustainable agronomic practices. It’s this mutually beneficial relationship between agricultural business, smallholder, and natural environment that’s at the heart of what we look for in our social and environmental due diligence process.

Specifically, agricultural businesses typically support producer livelihoods and ecosystems in one or more of the following ways, each of which is measured in our Social and Environmental Scorecards:

- Increasing prices to producers and wages to employees

- Increasing producer productivity

- Increasing stability of producer income

- Investing in or linking producers with public goods (e.g., health, education, water, transportation)

- Creating the incentives and delivering the training required to sustain producers’ ecosystems.

In regard to the environment, the locus of impact is the relationship between Root Capital’s clients and their farmer suppliers’ agronomic practices on the one hand, and the environmental integrity of the supporting ecosystem on the other. To the degree that those businesses and their suppliers invest in practices that maintain biodiversity, build soil quality, and responsibly dispose of waste, their ecosystems will continue to provide the services – the climate regulation, nutrients, and clean water – required for healthy livelihoods. Unsustainable practices such as excessive agrochemical use or nutrient mining have the opposite effect, and the mutually beneficial cycle between producer and ecosystem will eventually break down.

The business, as well as exporters, processors, retailers, and consumers, also benefit, as farmers provide stable and secure supply of agricultural products. Over time, a cycle of mutually beneficial repeat relationships throughout the value chain can emerge. Of course, the interests of the different players are not always aligned with one another, particularly over the short-term, and external factors such as commodity market volatility can disrupt these relationships. Nevertheless, to the extent that mutually beneficial relationships can be achieved in smallholder-based agriculture, the entire value chain will be more secure, resilient and sustainable.

For this mutually beneficial cycle to emerge – and for agricultural value chains to function well – many pre-conditions ranging from producer capacity to dependable logistics must be met. From our vantage point as a specialized agricultural lender, two value chain lubricants play a particularly critical role: trust and credit.

In the next post, we will dive deeper into the role that trust and credit play in the mutually beneficial cycle.

Check out the previous post in the series: What is Social and Environmental Due Diligence?